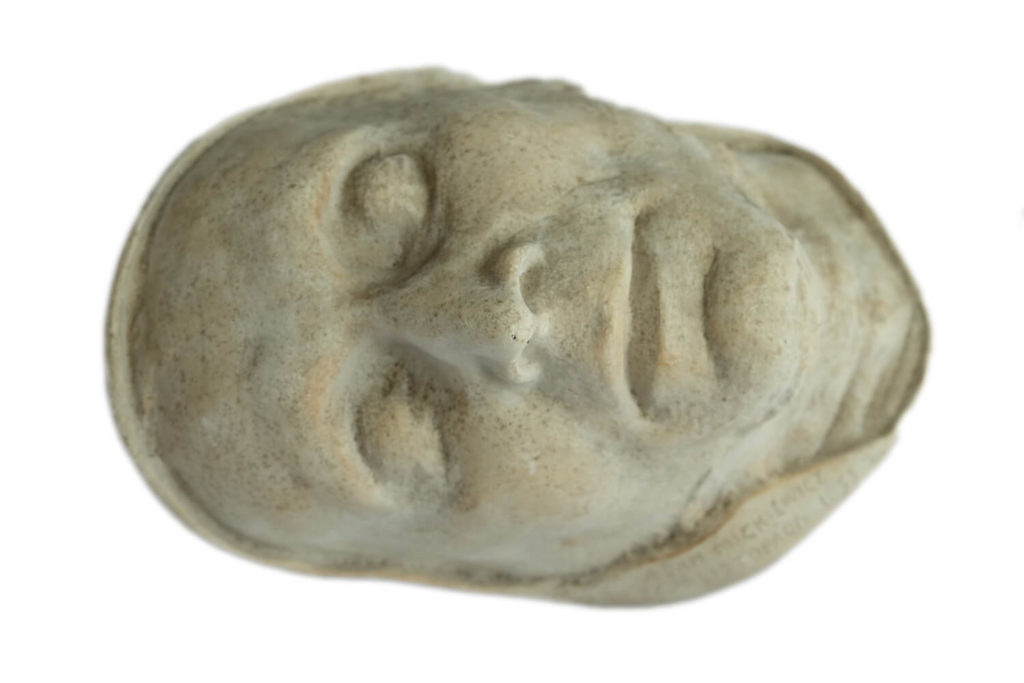

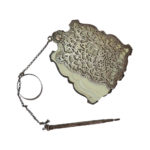

Adam Mickiewicz’s last-used pen

For centuries, a quill pen had been the most frequently used writers’ tool. In the 1840s, it was fitted with a metal nib which improved writing, reduced the tool’s wear and tear and the need to sharpen its tip which was dipped in ink. The object on display is Mickiewicz’s last pen which the poet had on him during his diplomatic mission to Istanbul in 1855. Following Mickiewicz’s sudden death, the pen returned to Paris along with its owner’s body, and is presently on display at the Polish Library in Paris. The object’s condition indicates that the poet used to sharpen the pen himself and did not use a nib.